Cotton, Empire, and the Code That Came Off the Loom

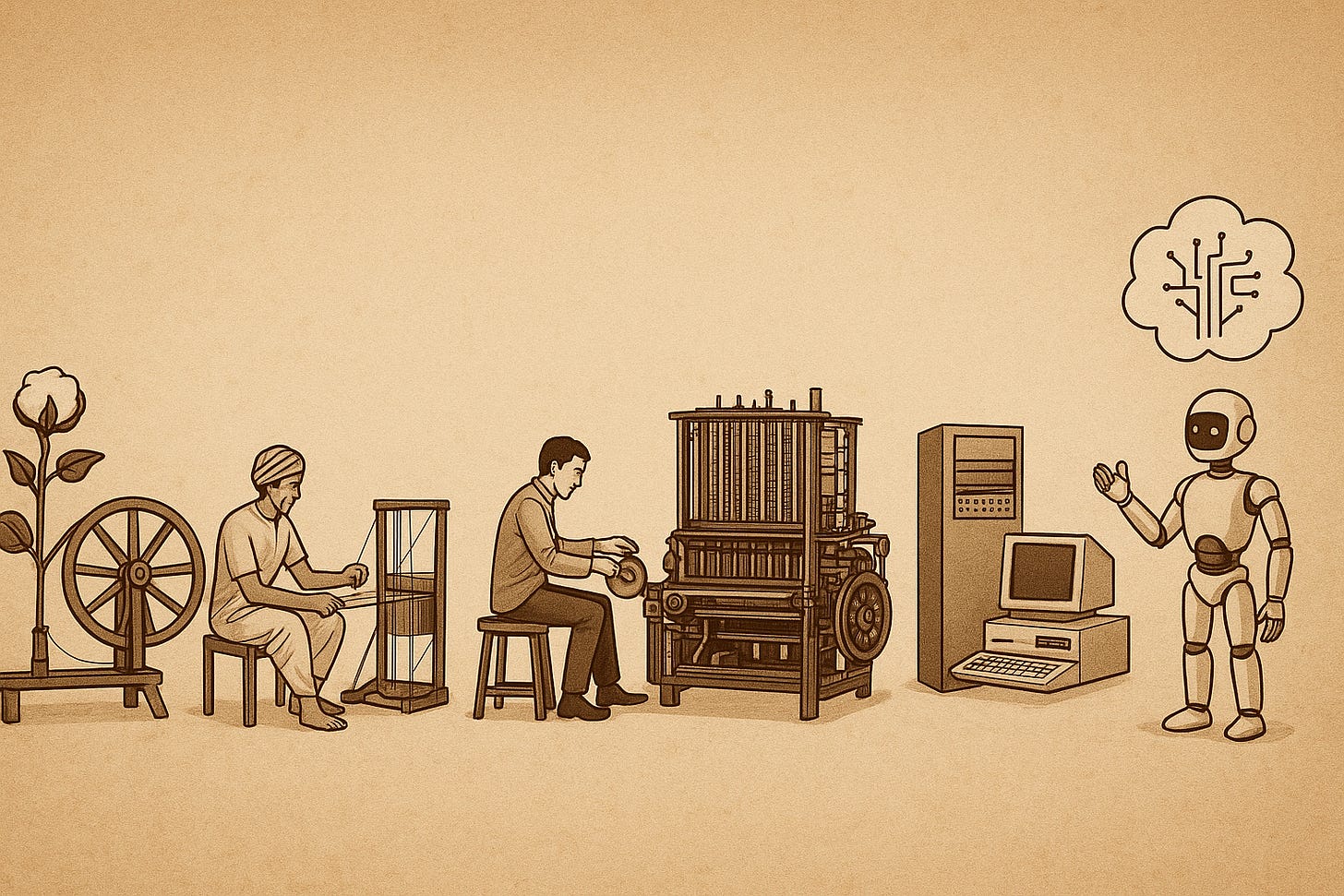

Threads of cotton to threads of code — a story of looms, empires, and machines, where fabric and memory weave the quiet architecture of modernity.

Hello 👋

Over the years, I’ve drifted in and out of writing — sometimes on X, sometimes on LinkedIn, and more recently on Medium — but consistency has been less than desirable. Long, winding essays have always been my thing. Too often they ended up as half-written abstractions abandoned at the tender age of 1,500 words. The luckier ones survived as ideas conceived and never put through the tyranny of keyboards.

This essay was born while I was reading Amitav Ghosh’s The Circle of Reason — an engrossing, immersive, and at times exhausting novel that pulls you so deeply into its world that you emerge tired from living inside it. In it, Balaram, a science-obsessed teacher, sends his orphaned nephew Alu to apprentice under a village weaver — a decision seen as a tragedy in an education-minded Bengali family. But Alu is overjoyed.

Why? Because, as Ghosh writes:

“Man at the loom is the finest example of the Mechanical Man; a creature who makes his own world as no other can.”

My imagination peaked when I read: “Think of cotton. It’s easy now, but it wasn’t once.”

And by the time I arrived at: “When the history of the world broke, cotton and cloth were behind it; mechanical man in pursuit of his own destruction,” this essay had already become inevitable.

TL;DR

If this note already feels long (a weakness I admit freely), then fair warning: the essay ahead is even more of a trek. You can always skip to the summary video at the end — courtesy of NotebookLLM. In the end, code wins.

Spinning the World: Cotton, Empire, and the Code That Came Off the Loom

History likes to pretend it moves on rails: empire, industry, technology—click, click, click. But the truth is messier, more human. It moves the way cloth is made: by hand and habit, by millions of tiny decisions, by threads crossing other threads until a pattern appears that nobody quite planned. If you want to see how the modern world was woven, start not with coal or steam or silicon, but with something humbler: a soft fibre pulled from a boll in an ancient field, twisted between thumb and forefinger, and set on a loom. Cotton is where the story begins; code is where it ends up.

It start from the Indus Valley around 3000 BCE. Cities are stacked like bricks along the rivers, drains run straighter than many modern streets, and in a quiet courtyard a weaver is teasing fibres into yarn. Archaeologists will later find the evidence: fragments of cotton clinging to copper beads, impressions of woven cloth baked into clay. It isn’t romantic; it’s technical. Cotton behaves. It takes dye well. It breathes. It can be spun fine without falling apart in your hand. The miracle is not that a plant could do this—it’s that a civilisation knew what to do with the plant.

By the time Herodotus is compiling his observations in the fifth century BCE, cotton has acquired the aura of legend. He writes, with barely concealed envy, of “trees in India that bear fleece more beautiful than that of sheep.” A poetic misdescription, yes, but a true one at the level that matters: India had the good stuff, and everyone else wanted it. Over the next millennium, routes braid themselves from the subcontinent across the Indian Ocean to Arabia and up through the Red Sea into Mediterranean markets. Cotton moves with spices and stories. Rome buys. Rome complains. Gold sluices east not because the East is mystical but because the cloth is better. That is the first lesson of the cotton trade: quality bends policy, and taste beats tariffs—at least for a while.

By the sixteenth century, taste has matured into mania. Europeans borrow words to describe what they cannot make: calico from Calicut, muslin from the tangled geography of trade where Mosul is credited but Bengal does the magic. In Dhaka, muslin is so fine it seems to hover over the skin. Banaras answers with brocades that catch candlelight at the right angle and flicker like water. Jamdani weavers embed pattern into pattern, producing fabric that looks as if it were embroidered by air. People like to imagine that such miracles are purely artisanal—genius fingers and hereditary secrets—but the craft is more rigorous than romance allows. There are systems beneath the surface.

Sit for a day in a workshop in Banaras and you will see the code. Not code as in a laptop; code as in an agreed-upon sequence that becomes a repeatable design. A master weaver murmurs a pattern. An assistant, often a child with a frighteningly reliable memory, lifts one set of cords, then another. Graphs scratched in chalk, the order of heddles, the discipline of the repeat—these are instructions, not inspirations. In Bengal, jamdani motifs do not emerge from trance; they execute from recall. The loom is a device that holds state. If that sounds suspiciously like a computer, it should. Before Europe mechanised the principle, Asia had embodied it.

Of course, the West arrives, and with it a familiar transformation: when you cannot match a rival’s product, you move the contest to policy. English wool and silk lobbies discover that Indian cotton threatens both livelihoods and pride, and Parliament obliges. The Calico Acts at the turn of the eighteenth century do what legislation often does when faced with superior foreign goods: they criminalise preference. For a time, the ban works in name but not in practice; smuggling is easier than re-educating taste. But the play is longer. You don’t just block the cloth—you capture the source.

The hinge turns in 1757, at Plassey. The East India Company wins a battle and takes a province; then it takes the fiscal levers; then it takes the terms of trade. India shifts—from exporter of finished textiles to supplier of raw fibre and captive market for British machine-made cloth. If you want to know what “deindustrialisation” looks like before economists coined the word, walk through Bengal in the late eighteenth century. Contracts that bind without escape. Advances that are really debts. Prices set by the buyer. Loaves shaved thinner each month. Floggings when a weaver tries to sell to a better offer. Looms smashed to clarify whose monopoly is being protected. Somewhere in there a story takes form, repeated enough times to harden into folk memory: thumbs crushed, fingers maimed, a craft broken at the wrist. Historians will argue over the literal frequency; archives will prove sparse where rage is abundant. But the metaphor catches because it is true in the most important way. Whether through knife or law, the hand that fed the world was pinned to the table.

Meanwhile, two other machines are getting to work. In Britain, at the very moment Indian hands are being tied, hands in Lancashire are being freed by iron and water. Spinning and weaving leap from the rhythm of the human body to the rhythm of the wheel. Hargreaves’ spinning jenny multiplies thread. Arkwright’s water frame tames the stream. Cartwright’s power loom moves the shuttle faster than a forearm ever could. The factory arrives not as a building but as a tempo. Cotton becomes the perfect feedstock for mechanisation because it behaves predictably—provided someone else absorbs the unpredictability. That unpredictability is offshored to fields.

Across the Atlantic, the second machine clicks into place. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, patented in 1793, solves the bottleneck no entrepreneur could think past: the labour of cleaning short-staple cotton. Ginned cotton scales the South, and slavery—briefly in political retreat—returns with an accountant’s confidence. The ledger clarifies the triangle: Indian fields for fibre, American plantations for volume, British mills for value addition. Manchester and Liverpool choose their civic nicknames with the charming literalism of the nineteenth century: Cottonopolis. The empire that lectures the world on free trade discovers that freedom looks like a tariff at home and a monopoly abroad and a whip on the plantation. All three are the same policy instrument.

There is a temptation, when telling this story, to stop at outrage. But outrage alone cannot explain what happens next on a different kind of loom in a different city. Lyon, 1804. Joseph-Marie Jacquard is not a philosopher of empire; he is a practical man solving a practical problem: silk patterns are complex, human assistants are slow, and errors are expensive. He looks at a long tradition—Chinese drawlooms where drawboys lift cords according to memorised sequences; Indian workshops where the memory lives in people and paper—and proposes the one change that turns a craft into a system. What if the instructions themselves could be made into an object? What if pattern could be stored and fed to the loom?

Punch a hole, don’t punch a hole. String the cards like beads in a necklace. Let the machine read the necklace. The beauty of Jacquard’s invention is not the device (ingenious though it is) but the abstraction it makes possible. A pattern now exists outside the weaver. It can be shared, bought, sold, archived, repeated. You don’t have to know the flower to weave the flower; you have to have the cards. This is the moment where textile history brushes the edge of epistemology: the shift from tacit knowledge—things you can do but cannot fully say—to explicit knowledge—things that can be encoded, indexed, copied.

You can feel why a mathematically minded Victorian would fall in love with this idea. Charles Babbage is many things—precocious, stubborn, perpetually short of money—but above all he is allergic to waste. The waste that offends him isn’t moral; it is mechanical. He stands over error-ridden logarithm tables and dreams up the Difference Engine to mechanise accuracy. When he graduates from numbers to the full symphony of calculation, the Analytical Engine requires a way to tell the machine what to do. Jacquard has solved the plot point: you don’t describe the operation each time; you feed the program. Punch the instruction, don’t punch the instruction. A chain of cards becomes a loop. A loop becomes a subroutine. Ada Lovelace—who understands Babbage’s system in a way he never quite manages—writes the first notes about what a general-purpose computer could be, and she does it with the metaphor that refuses to go away: the engine will weave algebraic patterns as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.

It’s a convenient metaphor because it is not merely a metaphor. Half a century later, Herman Hollerith discovers that the cards which stored patterns can store people. The 1890 U.S. Census is a data problem of scale, not of insight, and Hollerith’s machines solve it by embedding the facts of a person’s life—sex, age, birthplace—into the presence or absence of holes. The cards pass over electrical contacts. Where there is a hole, a circuit is completed. Data becomes counted at speed. A company is born that will later rename itself IBM, and for another half-century the hiss and clatter of card sorters will define the sound of information work. If you walked through an IBM hall in the 1950s and then through a weaving shed in Lyon in 1810, your ears would recognise the principle even if your eyes did not. The machine reads a memory from outside itself. The pattern is not in the hand; the pattern is on the card.

What does any of this do for the weaver in Bengal? Very little—and everything. Very little, because machine logic in England does not put rice on an Indian plate. Everything, because the chain that runs from Dhaka to Lyon to London to New York is a single idea moving through media: repeatability. The true commodity of the modern age is not cloth or coal or code. It is the ability to make something identical to itself a million times. Cotton happens to be the first arena where the world learned to scale that trick across oceans. The loom is the first industrial computer not because it calculates but because it executes. It internalises the step from intention to production.

In India, the response arrives not as a technological retort but as a political counter-argument. Gandhi does not pretend that a charkha can beat a power loom in throughput. He is making a different claim: that a nation cannot live on imports of its will. Spinning becomes a practice, a prayer with a product, a way of insisting that not everything must be outsourced to a machine owned by someone else. Khadi, cheap and honest, cuts two ways. It is self-reliance in cotton and also self-respect in cloth. The point is not to stop the factory; the point is to prove that the hand might still set the terms of its relationship with the machine. In that sense Gandhi anticipates the best version of modern technological politics: the insistence that language, rights, and ownership must keep pace with horsepower.

If we pull back, the historical irony is exquisite. Cotton sets the template for globalisation: specialisation, supply chains, arbitrage, and the ruthless disciplining of labour. But it also bequeaths the architecture for abstracting instructions from effort—the very leap that lets us compute. Without the loom’s grammar of holes and hooks, it is harder to see how nineteenth-century minds would have imagined feeding commands to brass and gears. Without the cards, it is harder to see how twentieth-century minds would have imagined feeding people to statistics. The technical and the political are not separate threads; they are the warp and weft of the same fabric.

And yet this is not a story about inevitability. At any number of junctions, choices could have been different. Britain could have chosen to compete on quality rather than prohibition when Indian cotton arrived on its shores. It did not; it legislated fashion. The East India Company could have chosen to nurture the industry it profited from. It did not; it squeezed until the craft gasped. America could have taken Whitney’s machine as an opportunity to accelerate free labour instead of fastening new chains. It did not; it found in cotton a reason to postpone its reckoning by another seven decades and another war. Technology offers leverage; politics chooses where to apply it.

The habit today is to treat computing as a rupture: a clean break from the dirt and sweat economy into a frictionless cloud. But you cannot understand what a server farm is without first understanding a mill. Both are machines for turning energy into standardised output at scale. Both require highly structured inputs. Both reward the ability to predict. When you write software for a platform designed by someone else, you are in a relationship that the Indian weaver would recognise instantly. You are brilliantly skilled and structurally disempowered. You live at the mercy of policy wrapped in the language of progress. The thumb need not be crushed to feel immobile; a change to the API will do.

So what do we do with this history beyond admiring its coherence? One answer is to rehabilitate the weaver as a protagonist of modernity rather than a casualty of it. The jamdani pattern is not quaint; it is a user interface for memory. The Banarasi brocade is not merely luxurious; it is a proof that complexity can be domesticated without being trivialised. And the Jacquard punch card is not only the ancestor of COBOL decks and Fortran stacks; it is a monument to the day we realised knowledge could travel separately from the knower. That realisation is dangerous and liberating in equal measure. It allows the apprentice to learn without whole lifetimes of apprenticeship. It also allows the owner of the cards to replace the owner of the hands.

Another answer is to take Gandhi’s provocation seriously in the age of platforms. Self-reliance does not mean everyone weaves their own shirt. It means we refuse to accept dependency as the natural state of technology. It means we insist that the costs of efficiency be visible, that local craft has a dignified lane in a global market, that the tools of abstraction—whether a pattern book in a loom house or an open model weight in a lab—do not become the exclusive property of those who can afford rent. If that sounds naïve, remember that the most naïve thing anyone ever said about cotton was that it was just cloth.

The counter-narrative you sometimes hear is that cotton’s link to computing is a loose metaphor stretched too far across two centuries. The rebuttal is empirical: Babbage says out loud that Jacquard’s cards suggested to him the method of feeding instructions; Hollerith says out loud that cards can hold data; IBM builds an empire on rooms full of card readers; early mainframes growl awake only when a tray of prepunched commands slides into place. If you want a clean genealogy from plant to program, there it is. But the more interesting continuity is cultural. Cotton teaches the world to prefer the same. It is the discipline of uniformity that makes both clothing sizes and compiled code plausible. Once you learn that a pattern can be made portable, you start designing the world around the distribution of patterns.

Cotton is also a morality tale without a clean moral. It gave Europe a path to industrial wealth and left India with the bill for a party it had hosted for centuries. It clothed the poor and enriched the cruel. It turned enslaved people into inputs and then, after emancipation, into expendables. It inspired a loom that elevated labour and a set of machines that deskilled it. It became a symbol of resistance and a symbol of scale. It is, in other words, the perfect teacher for a century that still can’t decide whether its tools will deepen human dignity or flatten it for margin.

Walk, finally, through a handloom cluster today. The rhythms are the same, the economics not much improved, the pride undiminished. A designer in Milan emails a pattern to a workshop in Varanasi; a laptop renders what a pattern book once carried; a warp is dressed; a motif returns that would make a Mughals’ courtier nod. Across the city, a startup founder writes code that will be compiled elsewhere and executed on machines he will never see. Both of them are in the same business: they convert intention into repeatable reality. Both depend on a chain of trust as long as the highway to the port. Both are grateful when nobody upstream changes the rules.

The thread that runs through this—call it cotton, call it code—has been tugging at us for five thousand years. It asks a practical question disguised as a philosophical one: who owns the pattern? In the Indus Valley, the answer was everyone; cloth was technology and technology was common. In the Company’s Bengal, the answer was: whoever can write the contract. In Lyon, it was: whoever has the cards. In the IBM hall, it was: whoever has the machine. And in our century, we are still arguing. Whoever has the model weights? Whoever sits on the marketplace? Whoever writes the policy that passes for “neutral”?

If you are inclined to pessimism, this story justifies it. If you are inclined to hope, it does that too. The weaver survives. The pattern travels. The cards are copied. The machine is reverse-engineered. The boy who once lifted cords on a drawloom now writes software that composes music with a prompt. The woman who once counted stitches now runs a cooperative. Histories of domination are never also histories of extinction. They are records of who was pushed aside while the machine rolled past—and who climbed onto it anyway and learned to drive.

Cotton still clothes half the world. It still exploits whoever is cheapest to exploit. It still dazzles when done right. And it still contains, in the fixed rhythm of its warp and weft, the whisper of what came after: that patterns endure, that memory can be made material, that instructions can live outside the person who knows them. That is not the origin story of computing; it is the origin story of modernity. The server rack and the jacquard head are two ends of the same machine.

We like to pretend that the future arrives from the future. It doesn’t. It arrives from the past, one card at a time. The loom taught us that. India taught the loom. And the world learned, at a cost it is still counting, how to spin a thread into a system. The cloth we wear and the code we run are not strangers; they are cousins. If you want a heritage beyond time, you could do worse than to hold a piece of muslin up to the light and listen to the holes in a punch card clicking as they pass the reader. That sound—soft and percussive at once—is history turning into instruction. It is the sound of a world being woven.

This is an AI Generated Video using NotebookLLM

Thank you for reading. If the essay resonated, please share it with someone who might enjoy it too — word of mouth means everything. I’d also love to hear your thoughts, whether in the comments here or over email.

I’m exploring ways to bring these essays to life in other formats — readouts, podcasts, voiceovers — to make them easier to consume. If you have suggestions, I’d love to hear them.

Thanks again for your time and attention.